What comes to mind when thinking of fungi such as mushrooms and fungi is that mushrooms are a favorite ingredient in various foods, and fungi are their ability to decompose dead organic matter into essential nutrients in shaded places without sunlight.

Recently, a research team at Virginia Tech in the United States has published a study highlighting the important role in Earth’s history that fungi helped the Earth revive from the frozen Ice Age in a wider field of view.

Research teams from the Chinese Academy of Sciences, Guizhou University of Education, and the University of Cincinnati, including professor Shuhai Xiao and Ph. like) Discovered the remains of a microscopic fossil.

It is the oldest terrestrial fossil ever discovered, dating back more than three times the best dinosaur fossils.

The discovery was published on the 28th in the scientific journal Nature Communications.

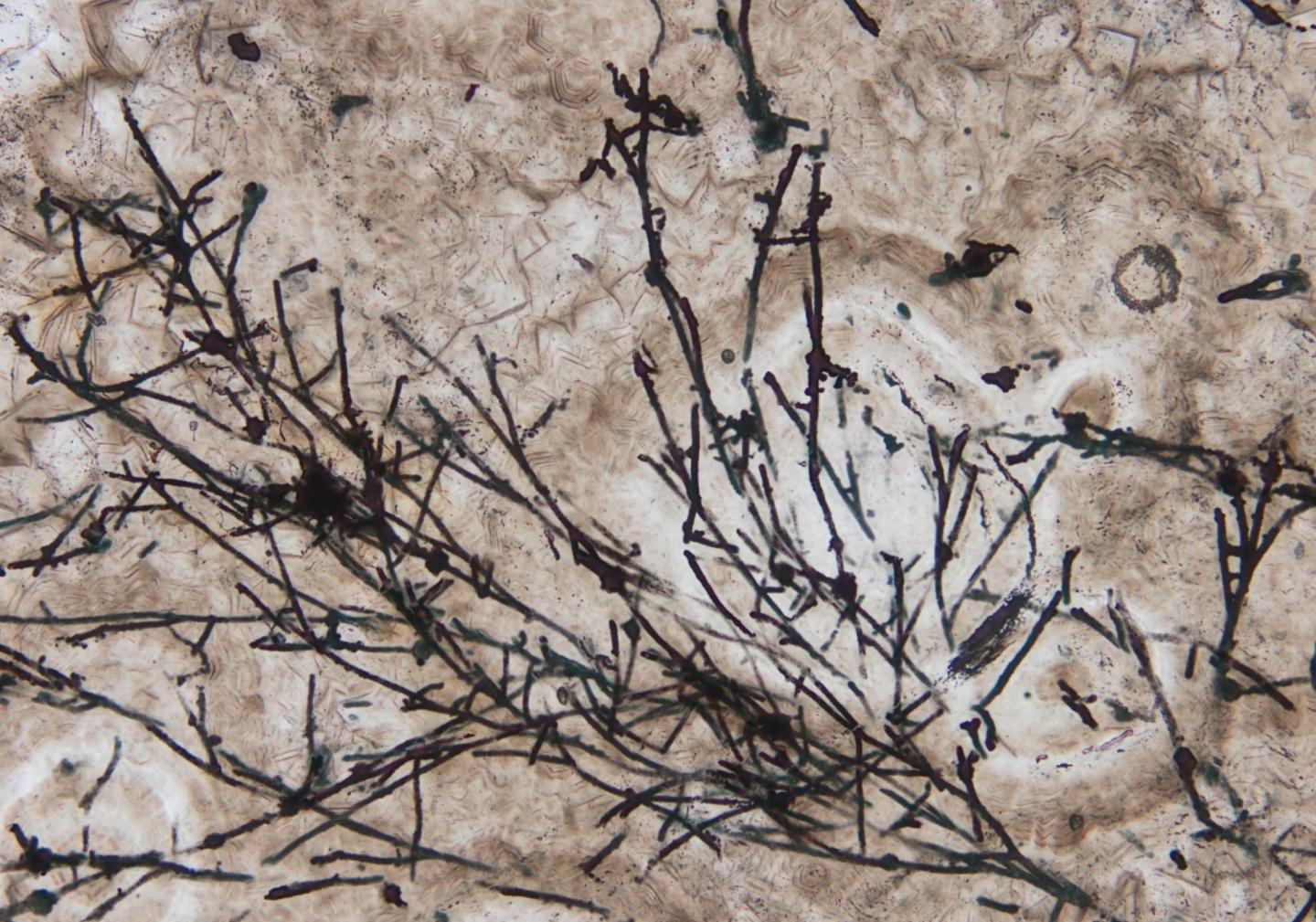

Microscopic image of a microscopic fossil with fungal hyphae found this time. © Andrew Czaja of University of Cincinnati

Unexpected discovery

The fossil was found in small pores in the doushantuo formation of the lowest doushantuo formation in Weng’an, Guizhou, South China.

Numerous soft tissue fossils were found in the Doushantuo Formation, and many studies have been conducted so far. Therefore, the research team thought that fossils could no longer be found at the lower base of the high ash rock.

However, breaking this expectation, Researcher Gan succeeded in discovering several long, thread-shaped filaments (hyphae), one of the key characteristics of the fungus.

“It was an accidental discovery,” said Gahn. “At the moment of discovery, I realized that this could be the fossil scientists have been looking for for a long time.” “If our interpretation is correct, this fossil will help us understand paleophalic changes and early life evolution,” he stressed.

Micro fossil micrographs viewed from the front, side, and back. © Tian Gan of Virginia Tech and Chinese Academy of Sciences

Important for understanding ediacaragi and fungal grounding

The findings are believed to be important in understanding the Ediacaran period and the terrestrialization of fungi, which have marked several turning points throughout Earth’s history.

The Ediacaragi is the last geological period of the Precambrian period that lasted from about 633 million to 541 million years ago, and it is known that multicellular organisms belonging to the Ediacara fauna appeared.

When the Ediacara period began, Earth was recovering from a catastrophic ice age called’snowball Earth’. At that time, the surface of the sea was frozen to a depth of more than 1 km. It was an incredibly harsh environment for almost all living things, except for a few microbes that could live in cold places.

Scientists have wondered how life was able to return to normal under these circumstances, and how the biosphere has since been able to grow larger and more complex than ever before.

A diorama of Ediakara sea creatures on display at the Smithsonian Institute, USA. © WikiCommons / Ryan Somma

244 million years older than the previous record

Researcher Tian and Prof. Xiao are convinced that the new fossil study would have played a number of roles in re-aligning the terrestrial environment of these subtle and inferior cave dwellers during the Ediacaran period. A powerful digestive system is one such role.

Fungi have a rather unique digestive system that plays a large role in the circulation of essential nutrients. The fungi living on the ground use enzymes secreted to the surrounding environment to chemically break down rocks and other harsh organic matter, recycle them, and then send them out to sea.

“The fungus has a symbiotic relationship with the roots of plants, so it can mobilize minerals such as phosphorus,” said Gan. “According to the linkage with terrestrial plants and important nutrient cycles, terrestrial fungi are It has a strong impact on the biogeochemical cycle and ecological interactions.”

Previous evidence suggests that terrestrial plants and fungi formed symbiotic relationships about 400 million years ago, but this discovery led to a readjustment.

Professor Xiao said, “Before the appearance of terrestrial plants, the question was asked whether there were fungi on the ground,” he said. “If you look at our research, you can answer’yes’.”

“The fungus-like fossils found this time are 240 million years older than previous records, making it the oldest record of terrestrial fungi ever found,” he said.

Fossil known as’Ediacaran embryo’ contained in single-celled marine fossils found in the Doushantuo Formation in South China. © WikiCommons

Need to understand organisms from an environmental perspective

The discovery prompted the research team to ask new questions. Since the fossilized filaments were accompanied by other fossils, Gahn plans to explore their past relationship.

“One of the goals is to find out the phylogenetic affinity of different fossils related to fungal fossils,” Gan said.

Few people believed 60 years ago that microbes such as bacteria and fungi could be preserved as fossils. Professor Xiao has actually confirmed these fossils with his own eyes, so he plans to explore how they were frozen at the time.

“The important thing is to understand organisms in an environmental context,” said Professor Xiao. “I generally think that these fungi lived in tiny holes in the gokaistone, but I don’t know exactly how they lived and how they were preserved,” he said. “I’m curious how things like bones or skinless fungi could have been preserved in the fossil record.” .

A thesis published on the 28th of’Nature Communications’. © Springer Nature / Nature Communications

“Young scientists should train from the perspective of interdisciplinary research”

The research team believes that it is still difficult to say with certainty that the fossils discovered are definitively fungi. There is considerable evidence to support this, but the investigation of this microfossil is still underway.

In this study, three research groups other than Virginia Tech also played an important role in fossil identification and timing. The Confocal Laser Scanning and Microscopy Lab at Virginia Tech’s Freilin Institute of Life Sciences helped Tian and Professor Xiao to do the initial analysis, and created an opportunity for further investigation at the University of Cincinnati.

In addition, modern fungal specimens from the Massey Herbarium of the Department of Biological Sciences at Virginia Tech, which contain specimens of more than 115,000 species of vascular plants, fungi, adenoids and lichens, were used to compare them with fossils.

To understand the fossilization environment, the research team analyzed the abundance of sulfur-32 and 34 isotopes with a secondary ion mass spectrometer, and advanced computed tomography obtained a three-dimensional form of fossil filaments that were only a few micrometers thick.

In addition, a fossil specimen was cut precisely by combining a focused beam scanning electron microscope and a transmission electron microscope, and the filaments could be observed in detail in nanometer units.

Professor Xiao said, “This study could not be carried out by one person or one laboratory alone,” stressing the importance of interdisciplinary collaboration.

“It is very important to encourage young scientists to train in terms of interdisciplinary research, as new discoveries always happen at the boundaries of different disciplines,” he said.

(1037)